Graphic arts in Japan

The introduction of Buddhism in Japan in 538 or 552 led to an iconography borrowed from the continent. Depictions of Buddha appeared on the walls of temples, on embroidered hangings and on objects of worship. In the Heian period (794-1185), religious painting developed considerably, in keeping with the iconographic conventions laid down by the new forms of Buddhism recently introduced from the Chinese continent (esoteric sects).

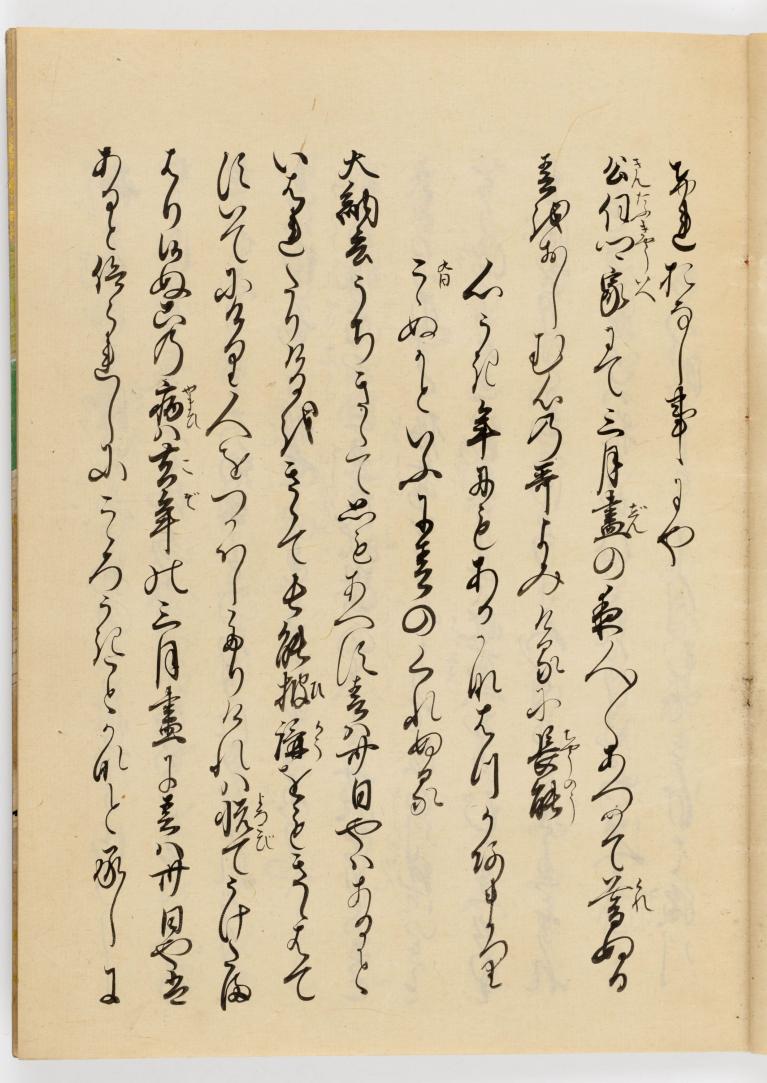

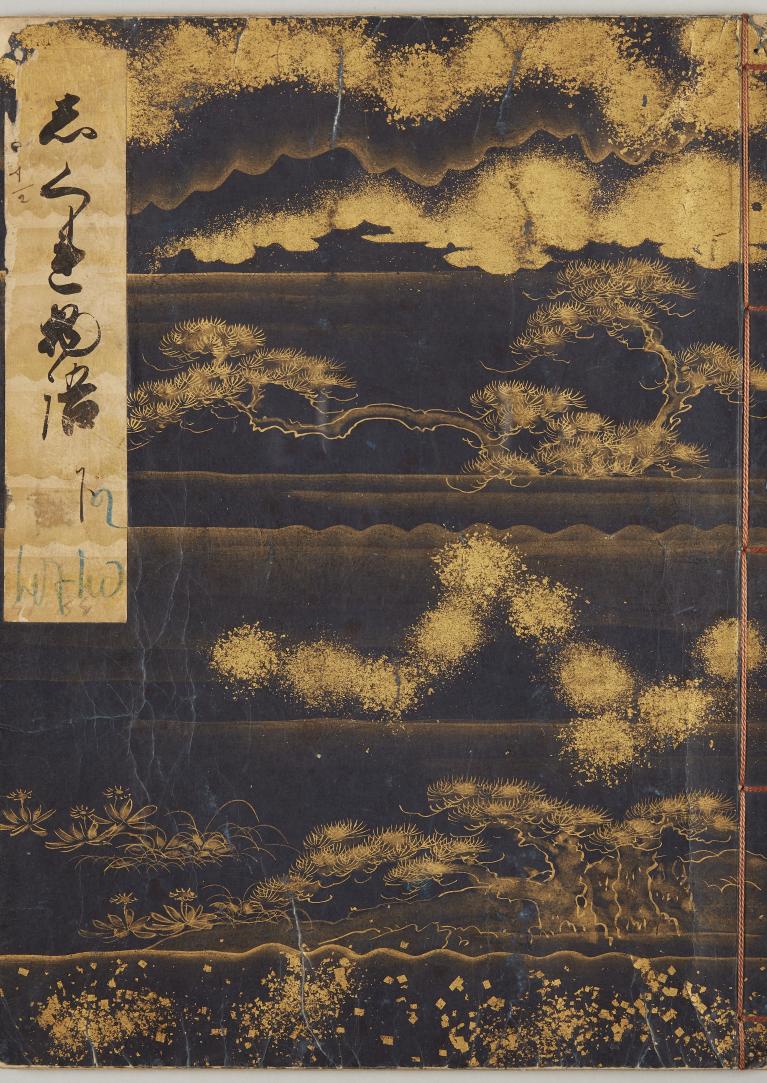

With the development of a syllabary writing system to transcribe the Japanese language came the emergence of a courtly literature, including its masterpiece, The Tale of Genji, written by a lady at court, Murasaki Shikibu, circa 1000.

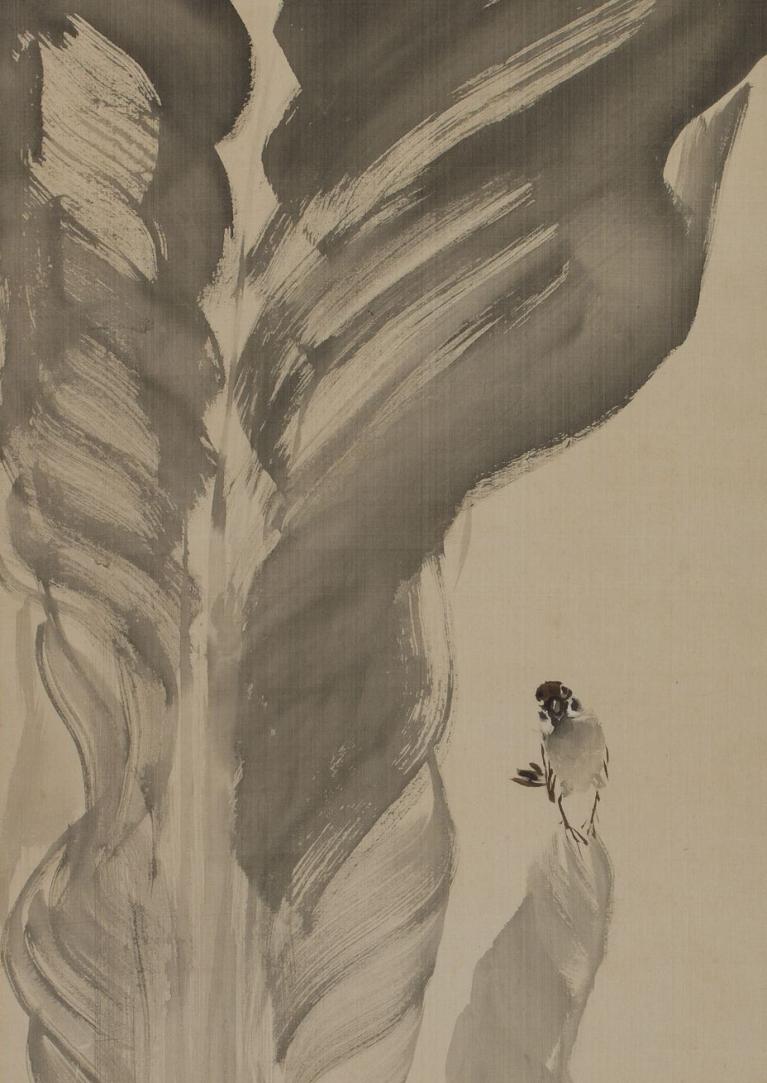

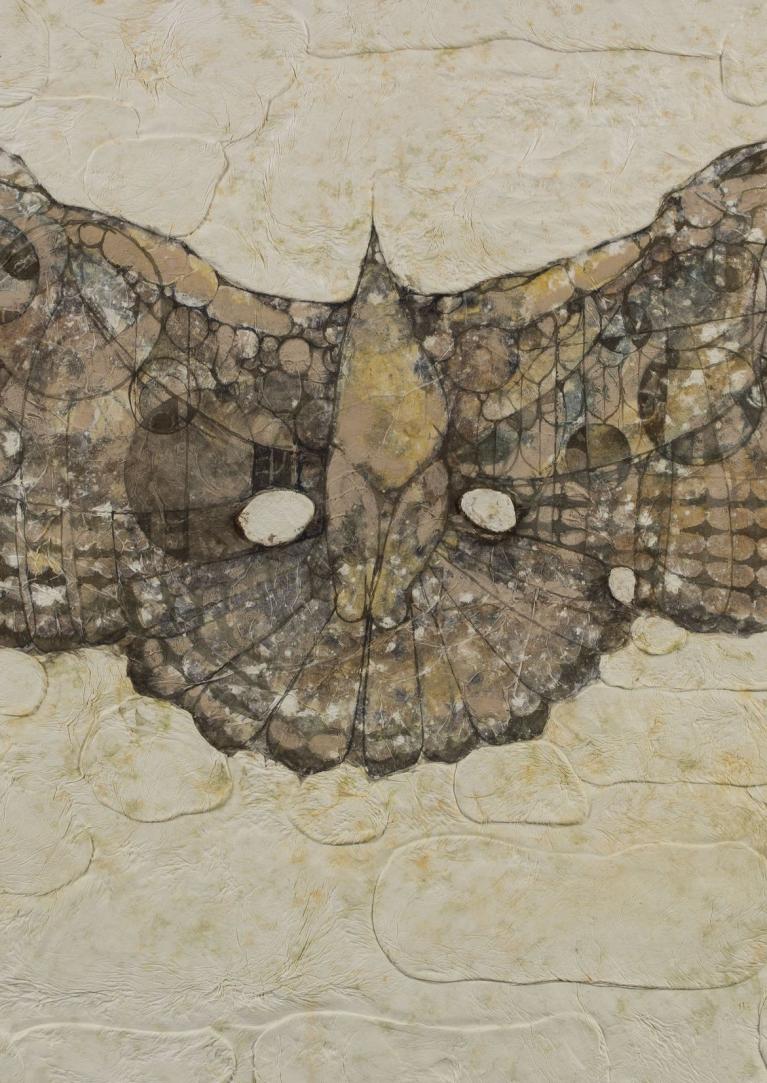

During the Muromachi period (1336-1573), the fashion for the Chinese aesthetic, under the influence of Zen Buddhism, fostered the development of monochrome ink painting. This style spread to the interior decoration of the shogunal palaces. The Kanō school of painting founded by Kanō Masanobu (1434-1530) executed these commissions. The painter Tawaraya Sōtatsu (active circa 1640) was largely responsible for the renewal of the themes illustrating classical literature. His bold compositions, with their broad expanses of colour and geometric forms, broke with the miniaturist tradition of the Tosa school and took Japanese painting into a new era. His style was perpetuated by artists that are often grouped under the Rinpa school and who were active from the late 17th century.

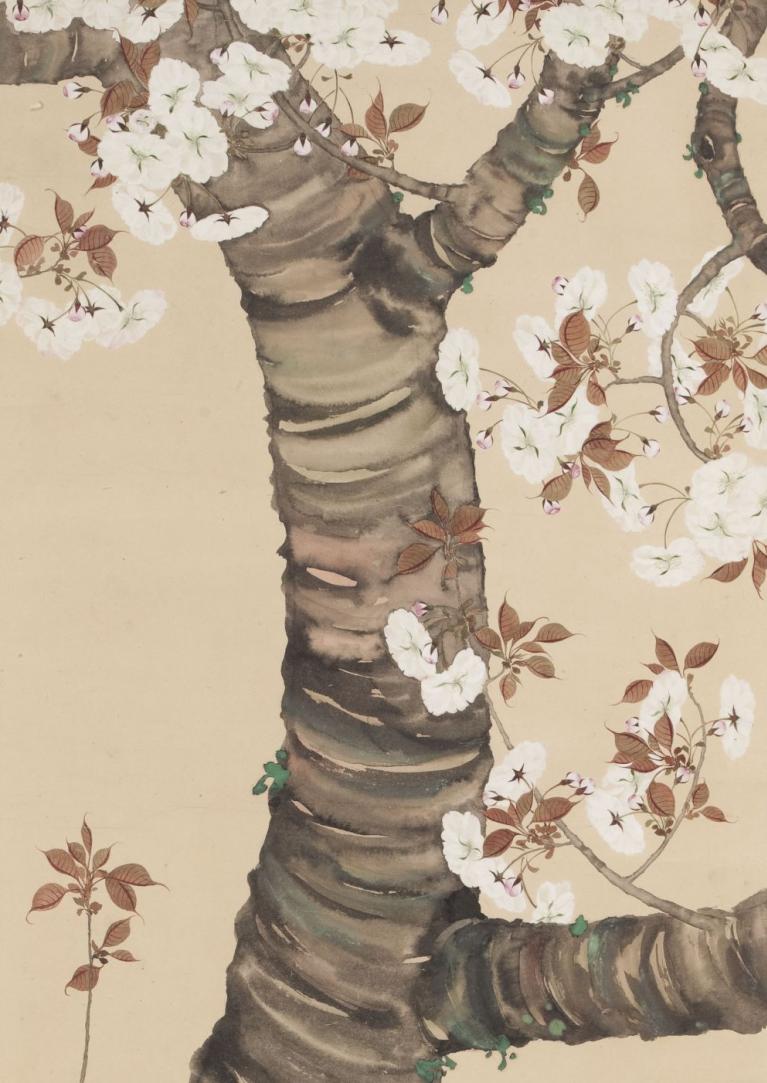

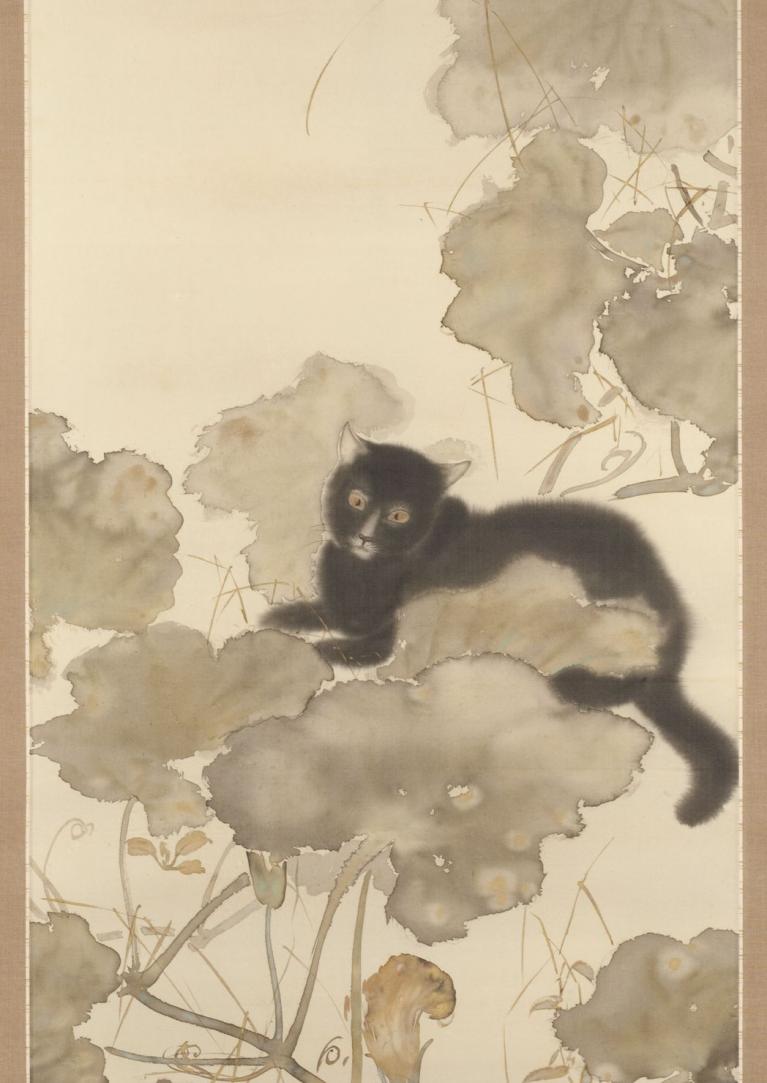

The introduction of Western paintings and prints from the late 16th century onwards and especially in the 18th century brought new themes and changed the perception of certain painters. In Kyōto, this realist movement (shaseiga) influenced the Maruyama-Shijō school founded by Maruyama Ōkyo (1733-1795). It paved the way for modern painting.