Giao Chỉ (Jiaozhi) period

The Giao Chỉ 交趾 period takes its name from that of the prefecture established in 111 BC in the Red River basin, on the conquest of the region by the Chinese Han emperor Wudi 漢武帝. This date traditionally marks the beginning of the influence of Chinese culture in Vietnam.

Yet this influence took hold much more progressively. Since the Warring States period (475-221 BC), China had experienced such political turmoil that the princes of the defeated kingdoms were taking refuge with the royal courts of the south. The first kingdom of Vietnam known to history, Âu Lạc 甌貉, was founded in 258 BC by a deposed prince from the north, An Dương Vương 安陽王. Then the First Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huangdi 秦始皇帝, undertook to conquer the north of Vietnam, attracted by its riches. He sent one of his generals, Zhao Tuo (Triệu Đà 趙佗), who founded the kingdom of Nanyue (Nam Việt 南越) there in 208 BC.

In 111 BC, Emperor Wudi of the Han dynasty took up Shihuangdi’s dreams of conquest and, following a local rebellion, subjugated Nanyue.

However, the aristocracy of the Đông Sơn culture had continued to occupy key positions in the running of the country both under the Zhao, then in the Giao Chỉ period. Only imperial officials settled there; the inhospitable climate and remoteness discouraged Chinese tradesmen from establishing themselves. For this reason, the region did not undergo any major cultural upheaval before the early Christian Era.

But in 34 AD, two sisters, Trưng Trắc 徵側 and Trưng Nhị 徵貳, rallied the native aristocracy, which had been stripped of its privileges in the face of growing Chinese immigration. In 43 AD, the rebellion was violently supressed, and the region placed under direct control. From the second half of the 1st century, the Chinese custom of burying their dead in brick tombs took hold in northern Vietnam.

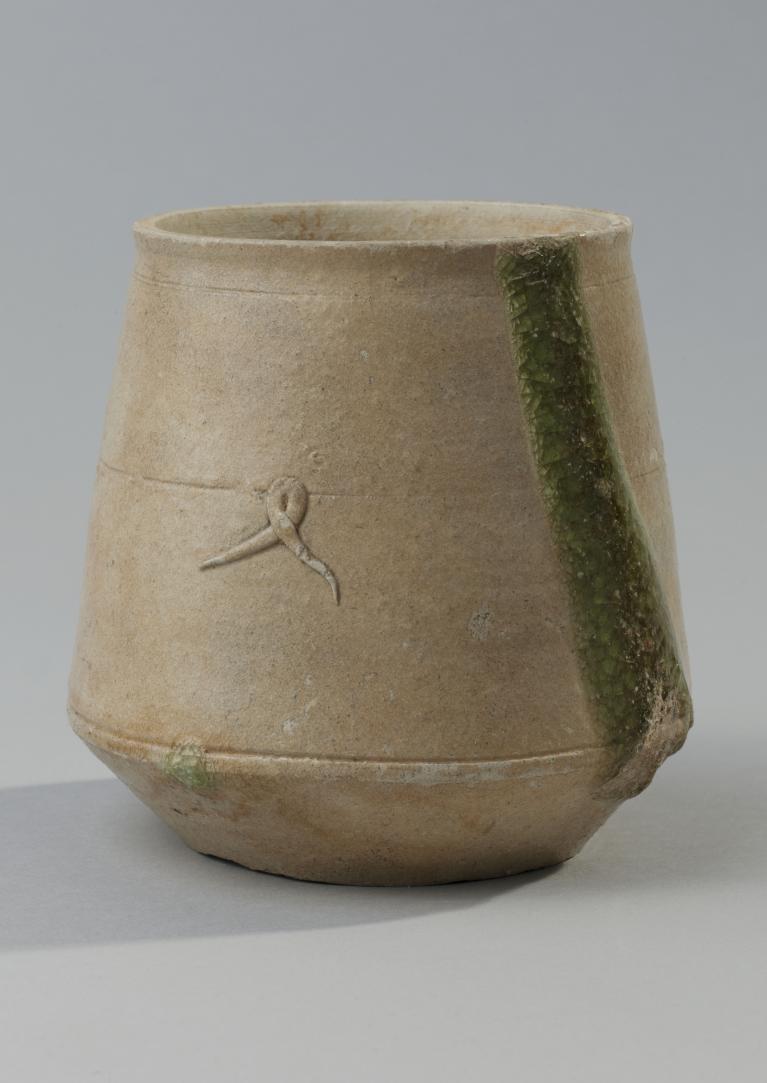

Tomb furnishing in the Chinese manner was a new means for the local aristocracy to express its social prestige, without renouncing its own identity. Numerous objects reflect the slow intermingling of Đông Sơn and Chinese traditions.