Modern and contemporary period

The 19th century was marked by the increasing influence of the French at court. Their modern techniques in terms of organisation and armament interested the Nguyễn rulers, but the growth of Catholicism since the 17th century, as a result of the French presence, was seen as a threat to Confucianism. Using the repressive campaigns against Christians as a pretext, French army raids weakened the country from 1858. By 1887, French domination was well established on the Indochinese peninsula. Vietnam was made up at the time of French Cochinchina in the south and the French protectorates of Annam and Tonkin in the centre and in the north, where the Nguyễn emperors were kept under tight control by the French.

During the first half of the 20th century, certain political leaders sought national independence, while at the same time Marxist ideas were beginning to take hold. In the artistic sphere, the French period saw the establishment of a network of specialised vocational schools for artists and craftsmen. The first schools, founded at the very beginning of the 20th century, were specialised in handcrafts. In the north, the Hanoi vocational college, founded in 1902, had two departments: one trained students in the professions of cabinetmaking, carving and chasing, foundry, mechanics and electricity; the other taught sculpture, embroidery, gold- and silverwork and ceramics. In the south, not far from Saigon, the school in Thủ Dầu Một, founded in 1901, offered training in cabinetmaking, and the Biên Hòa school, founded in 1903, was specialised in ceramics.

At the time, deep-rooted prejudice in the mentality of French officials denied the Vietnamese any artistic legitimacy. They entrusted them only with handcrafts—that is to say, reproductive arts as opposed to creative arts. It wasn’t until 1913 that a college with a more specifically artistic focus was established: the Gia Định school was founded on the initiative of André Joyeux, an architect and graduate of the Paris Beaux-Arts, who was its first director. The school served henceforth as a preparatory course for specialisation at one of the three schools of applied art in the region. After this initial year of general studies, based on drawing technique, students had to choose their specialisation for a six-year program: Gia Định for decoration, engraving or lithography; Biên-Hòa for ceramics and foundry; Thủ Dầu Một for sculpture on wood, inlay, marquetry and lacquerwork.

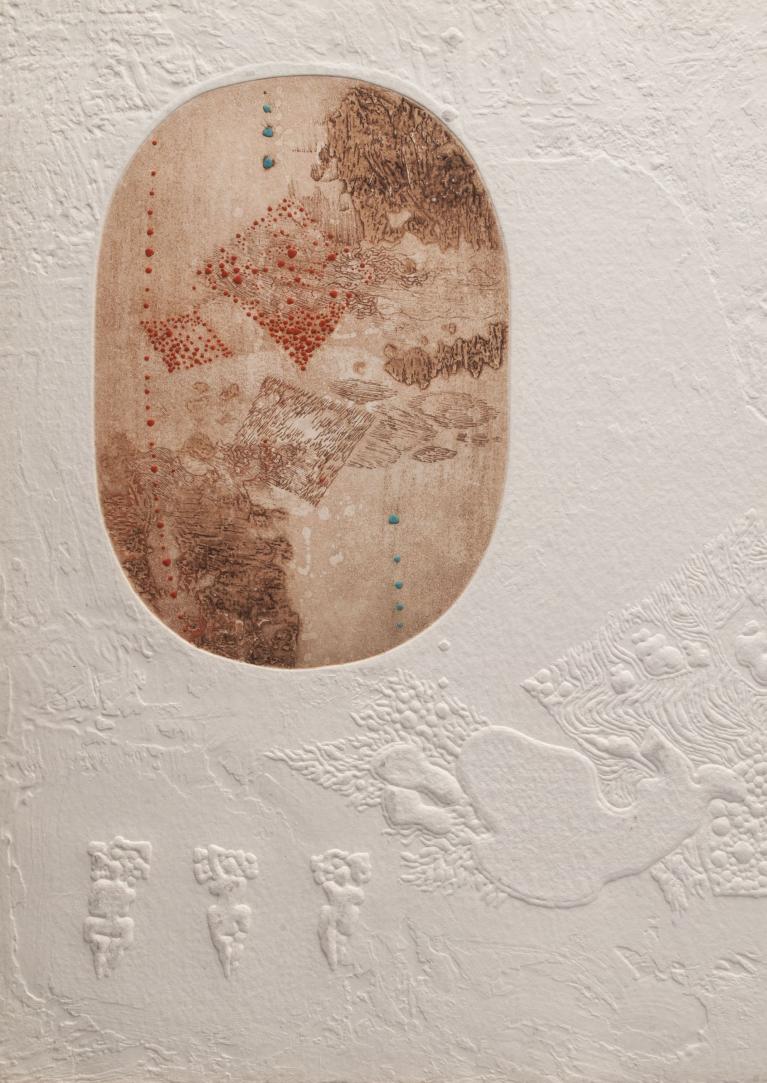

In the north, the painter Victor Tardieu (1870-1937) established the École des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine in Hanoï in 1925, with the painter Nam Sơn (1890-1973). The teaching, based on the model of Paris’s École des Beaux-Arts, aimed to achieve a synthesis of Western art and Indochinese tradition that would spawn a new and modern style infused with an authentic local spirit.

Following the colonial period and its Indochinese art came the art of wartime. In 1940, the Japanese entered Vietnam. After the Japanese defeat, on 2 September 1945, Ho Chi Minh declared independence and the creation of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. But the French regained their foothold in Indochina in October 1945. From December 1946 to the summer of 1954, the First Indochinese War divided the country. After France’s defeat, the country was split in two: the communist government in the north (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and the nationalist government in the south (the Republic of Vietnam). In the north, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam promoted the aesthetics of Socialist Realism and propaganda art inspired by the USSR and China. Hanoi, formerly at forefront of the Vietnamese artistic scene, now operated censorship: the nude, abstraction and surrealism were forbidden, and portraiture, still life and picturesque interiors were considered suspect.

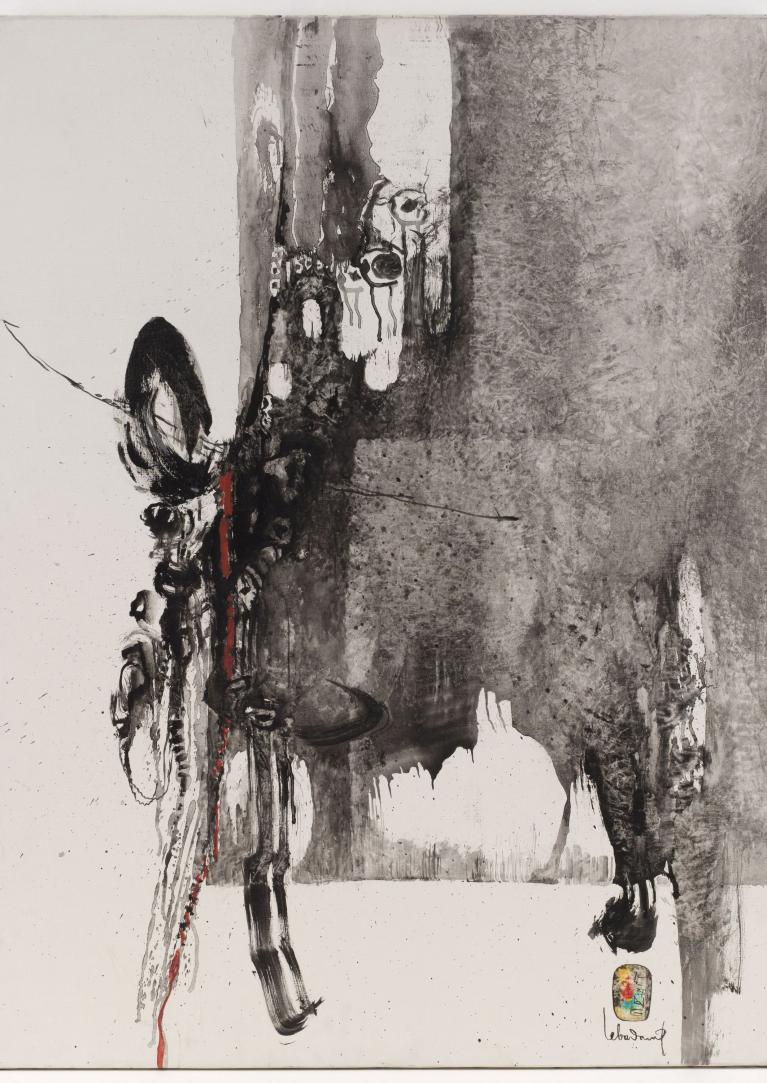

In the south, the Republic of Vietnam had not undergone as tight control as Hanoi between 1954 and 1975. Saigon was relatively independent and open at the time, and a style highly influenced by Western styles of the modern period, encompassing abstraction, cubism and surrealism, was the focus of artistic research.

The Vietnam War lasted from 1959 to 1975. In 1965, the United States sent in troops with the support of the government of the south. The government of the south was defeated by the communist troops. In successive waves, many Vietnamese went into exile. On 2 July 1976, the country was at last reunified as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, with Hanoi as its capital.

The 1980s saw the end of the dogmatism of Socialist Realism, with the sweeping program of Đổi Mới, or “Renovation”. In a swing of the pendulum, artists broke violently with commissioned art, and embarked upon a frenzy of artistic experimentation, with no clear single line of research. At last they encountered, and all at once, Western art from Picasso to Warhol, and assimilated, with many years’ delay, realism, surrealism, expressionism, pop art and minimalism. Tired of political subjects and propaganda, they developed the themes that had been banned – the nude, self-portraits, urban landscapes, ethnic minorities – extolling values that were more individual and more universal. This “painting of the Renovation”, “hội họa Đổi Mới”, propelled Vietnam onto the international art scene. Exhibitions were organised abroad, foreign collectors flocked to Vietnam and numerous galleries opened in the early 1990s in Hanoi, Hue and Ho Chi Minh City. Many artists were independent at the time and some managed to earn a living through their work, albeit a meagre one.

In the late 1990s, the initial effervescence gave way to a decline in painting. Galleries turned into souvenir shops, for lack of a demanding local clientele. Today, in the absence of state support for independent artistic production, Vietnamese art earns recognition through work that complies with the codes governing the major international events.