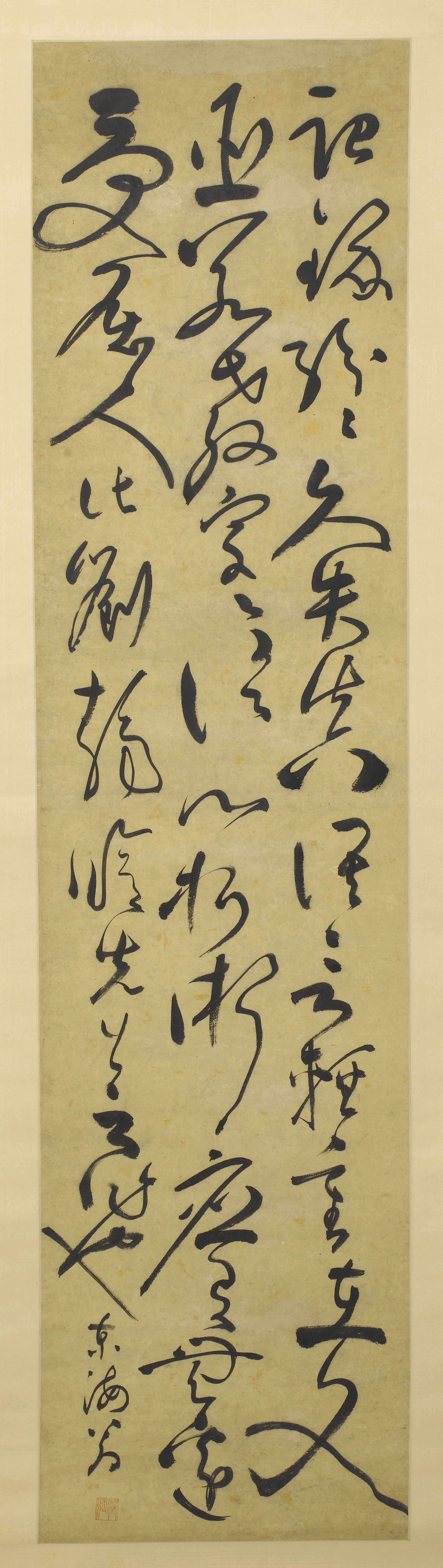

Calligraphie

Encre, Papier

Calligraphie

東海翁; 汝弼

Achat

M.C. 9253

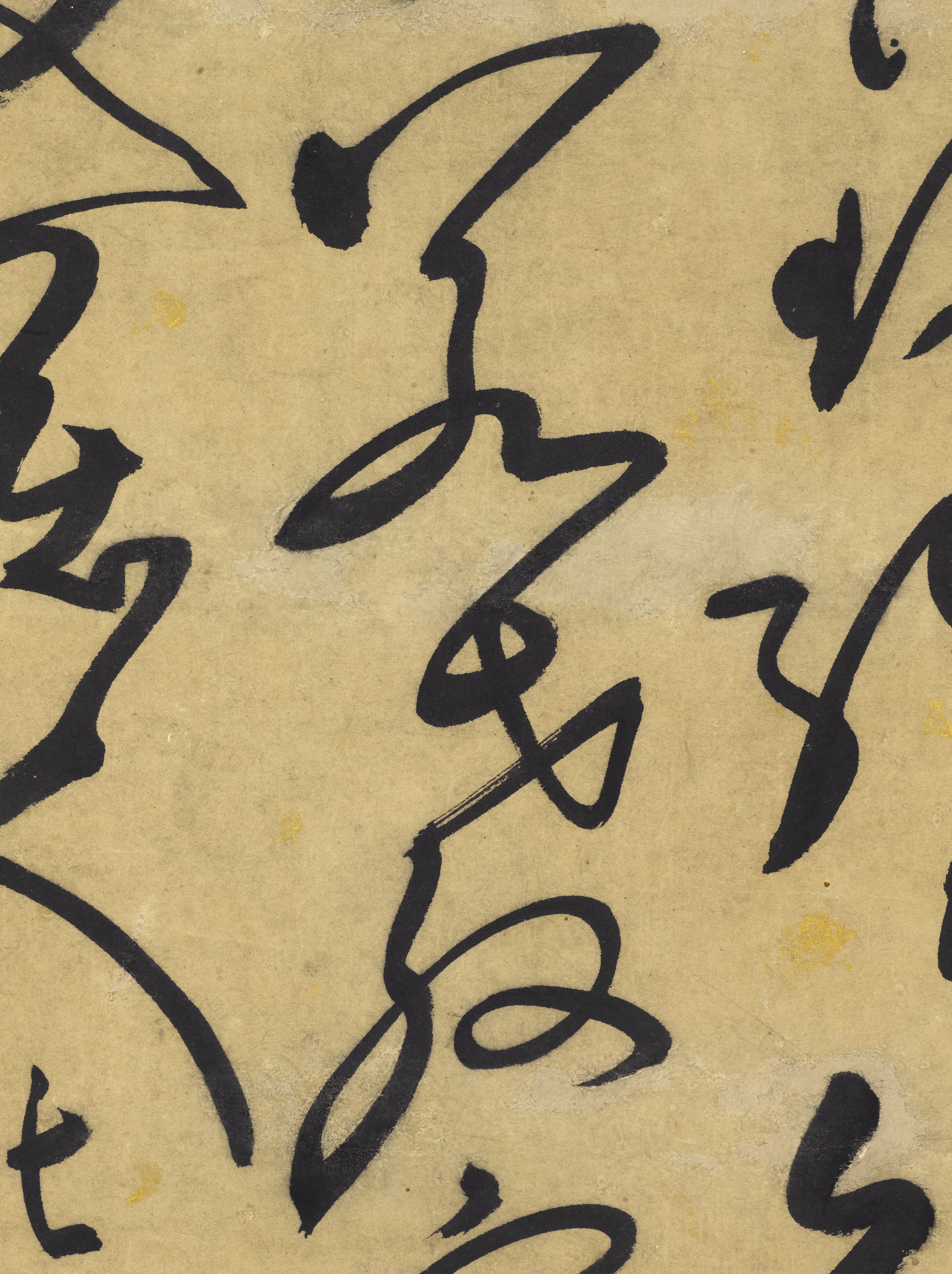

Inscription and signature 款識:紀錄紛紛久失真,語言輕重在文臣。若教字字論心術,應有無邊受屈人。此劉翰林先生之作也。東海翁。

Calligrapher’s seal 印:汝弼 (朱文)

Translation: Muddled and confused annals have long moved away from the truth, lettered subjects must measure the meaning of words. Literal interpretations of their spirit will necessarily cause harm to many. The words of the scholar Liu. Donghai weng (literary name of Zhang Bi).

Zhang Bi, a man of letters, poet and calligrapher, was born in Huating 華亭 in Jiangsu (modern-day Songjiang 松江). He took his jinshi examination in 1466. After occupying official functions in the capital his career encountered various setbacks, and he was posted to Nan’an 南安 in Jiangxi in 1478. For six years, he was the governor of this remote region, before retiring to his native region where he lived his final years.

Zhang Bi would say that his calligraphy was inferior to his poems, and his poems were inferior to his prose. Yet he was one of the foremost calligraphers of his time, with his contemporary Zhang Jun 張駿. His style, forged through the study of work by the early Ming calligraphers such as Song Guang 宋廣 and Chen Bi 陳璧 , would evolve as it drew inspiration from Tang artists, particularly Huaisu 懷素 (circa 735-800?). Zhang Bi’s wild cursive calligraphic work, which preceded by a few years that of Zhu Yunming 祝允明 (1460-1526), constitutes a key marker in the history of this genre in the Ming period.

This calligraphic work in the Cernuschi Museum, signed under the artist’s literary name Donghai weng (“Old Man of the East Sea”), dates from Zhang Bi’s mature period. In this example of wild cursive calligraphy, kuangcao 狂草, the artist appears to have moved away from the Huaisu influence: the work is executed in a personal style with a pronounced rhythm marked by varying thicknesses of the brushstroke. His large characters give the work’s layout a monumentality of his own invention.

The verses transcribed by Zhang Bi emphasise the responsibilities of the scholar, who must reinterpret the texts in order to pass on an accurate conception of history. These verses written by Liu Yin 劉因 (1249-1293) should be considered in the light of their historical context, that of the dynastic transition of the 13th century. This scholar and public official was witnessing the fall of the Song empire. He retired from public life shortly after the Mongols’ accession to power. His poems, which reflect his admiration for Ouyang Xiu 歐陽修 (1007-1072), Huang Tingjian 黃庭堅 (1045-1105), and Su Shi 蘇軾 (1037-1101), express his nostalgia for the golden age of the Song.

Eric Lefebvre, Six siècles de peinture chinoise, œuvres restaurées du Musée Cernuschi, Paris Musées, 2008, p. 20-21