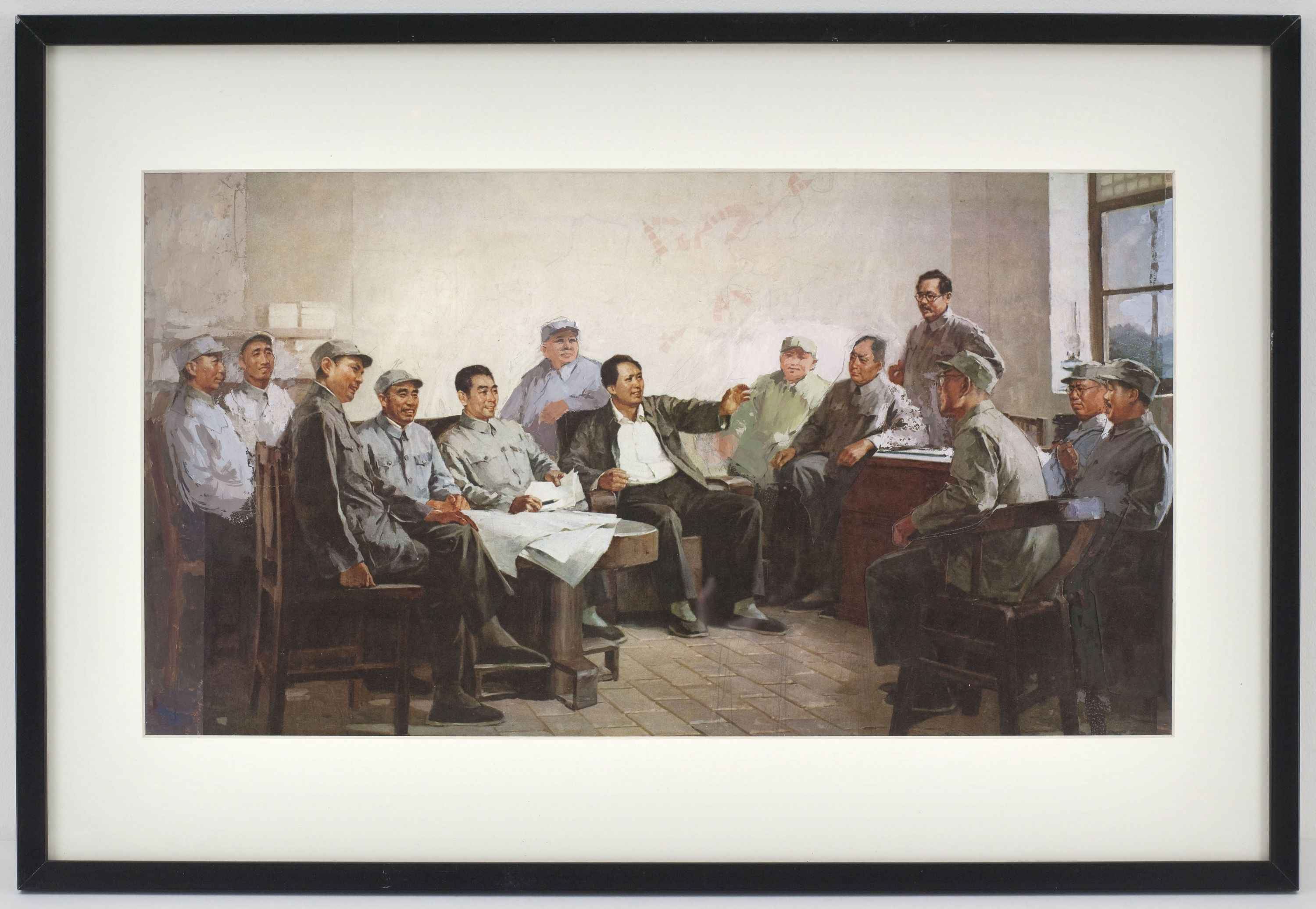

"Saisir la victoire dans tout le pays – le président Mao avec ses cadres" (esquisse)

Gouache

Peinture

Don manuel : Montres DeWitt SA; Galerie Hadrien de Montferrand

M.C. 2013-21

Yin Rongsheng is associated with an artistic tradition formalised in a speech given by Mao Zedong at the Yan’an Conference on Literature and Art in 1942, advocating the effacement of the artist’s individuality and artistic ambitions in favour of ideological objectives. The style favoured and encouraged by the Communist Party would be that of Soviet Realism, which was disseminated by the Beijing Central Academy of Fine Arts throughout the 1950s.

Yin Rongsheng, who graduated from this academy in 1954 and taught there until 1994, was long influenced by this ideology and the necessity of always adapting the content of one’s works to political requirements. As a result, he was among the artists commissioned by Luo Gongliu in 1961 to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the People’s Republic of China. With the opening up of China in the 1980s, he obtained a grant to study at Paris’s École Nationale des Beaux-Arts, and won new recognition in his country thanks to his writings on the paintings in the Louvre and Orsay museums.

In 1977, just after Mao’s death, a certain number of disgraced cadres were rehabilitated. Yin Rongsheng undertook to paint a fictitious meeting between these figures and Mao Zedong, still a major source of legitimacy. He donated the painting to the National Museum of China and it was reproduced for propaganda purposes. Shortly afterwards, the Revolutionary Military Museum of the Chinese People’s Revolution commissioned a second version of the work from him in order to include other recently rehabilitated figures. The additions notably included Peng Dehuai and, especially, Liu Shaoqi, rehabilitated in 1980 and an exemplary victim of the Cultural Revolution.

Yin Rongsheng used poster reproductions of his 1977 painting, reworking them in gouache to create his new composition. His hesitations in placing the figure of Peng Dehuai and the squaring of the work for transfer are visible.

This painting is highly representative of an art work closely controlled by the central power and the artist’s adaptation to the slightest ideological changes of the regime. It also proves that post-Maoist artistic emancipation did not constitute a homogeneous movement and that the older generations trained in the 1950s and 1960s perpetuated models developed thirty years earlier. This explains the existence today of an official art derived directly from this type of revolutionary painting.