Sui and Tang dynasties

Sui dynasty

Yang Jian, a general under the Northern Zhou dynasty, set about reconquering the northern territories, and founded the Sui dynasty in 581. In 589, he defeated the armies of the Southern dynasties, reunifying the whole of China. The Sui dynasty laid the foundations for a powerful state, which would flourish under the following Tang dynasty (618-907). The choice of Chang’an and Luoyang, former Han era capitals, as the Sui’s new capital cities, reflected a desire to restore the grandeur of the Han empire. This period of peace enabled the central government to begin reforms and large-scale public works, such as the digging of the Grand Canal between the Yellow River in the north and the Yangtze in the south, and the building of the Great Wall. However, seeking to re-establish the Han era borders, the emperor undertook military campaigns that proved ruinous and which would bring about his fall.

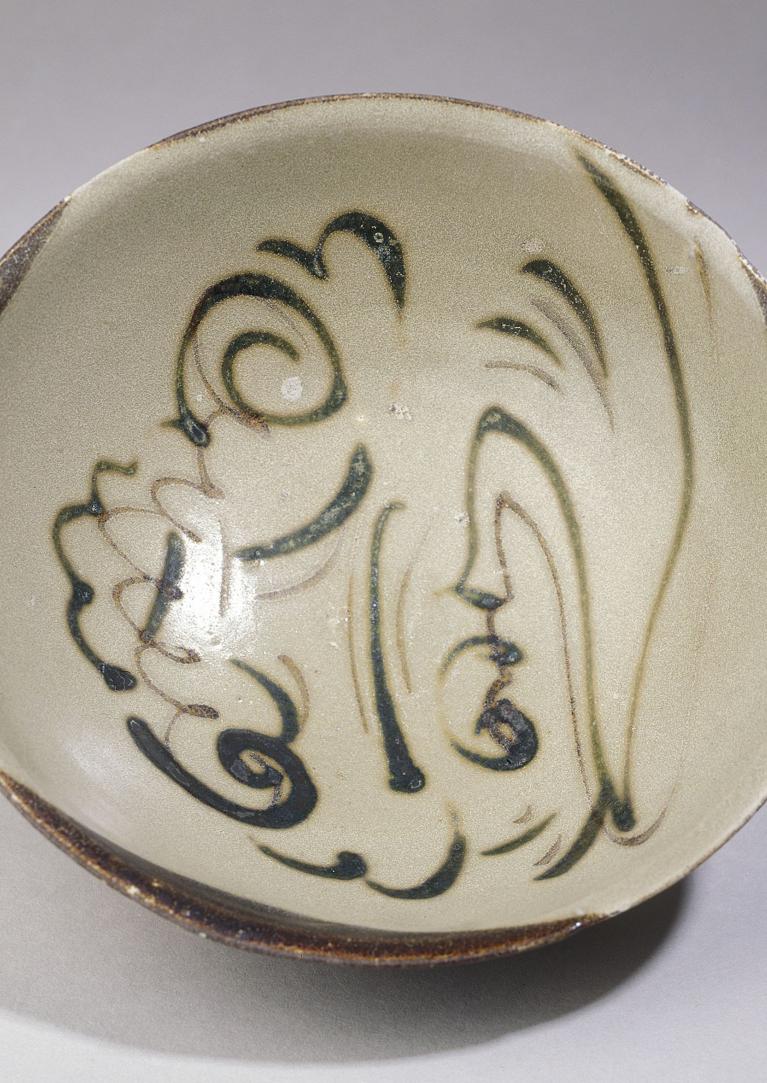

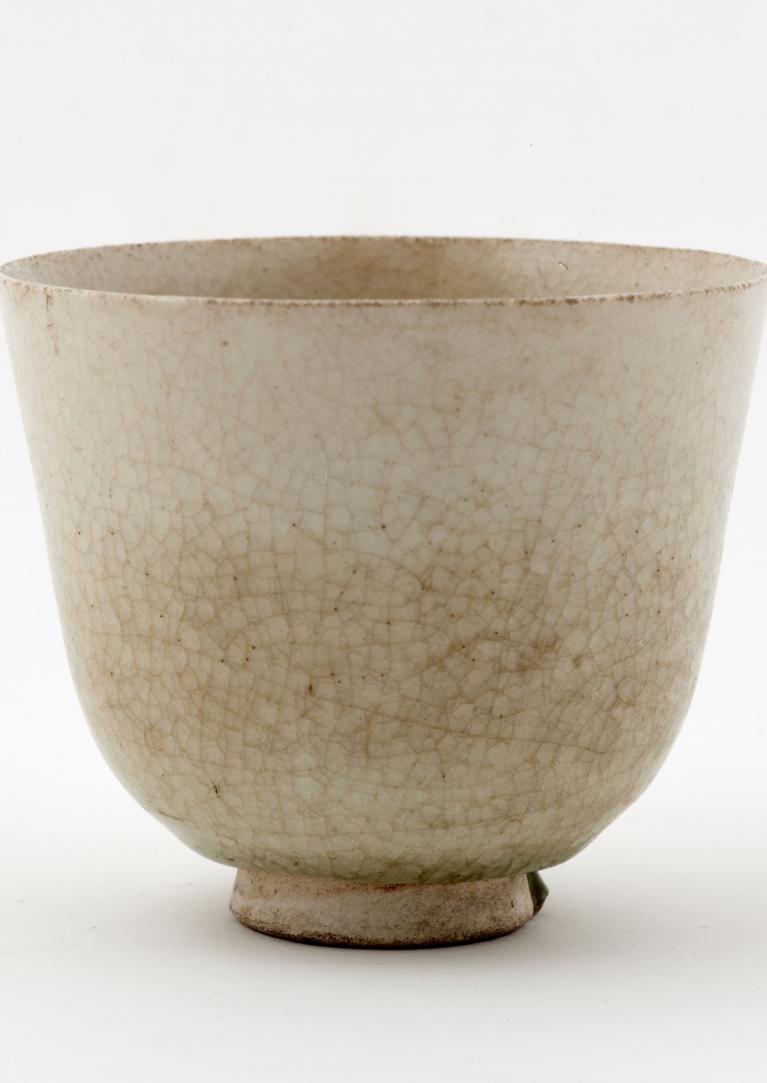

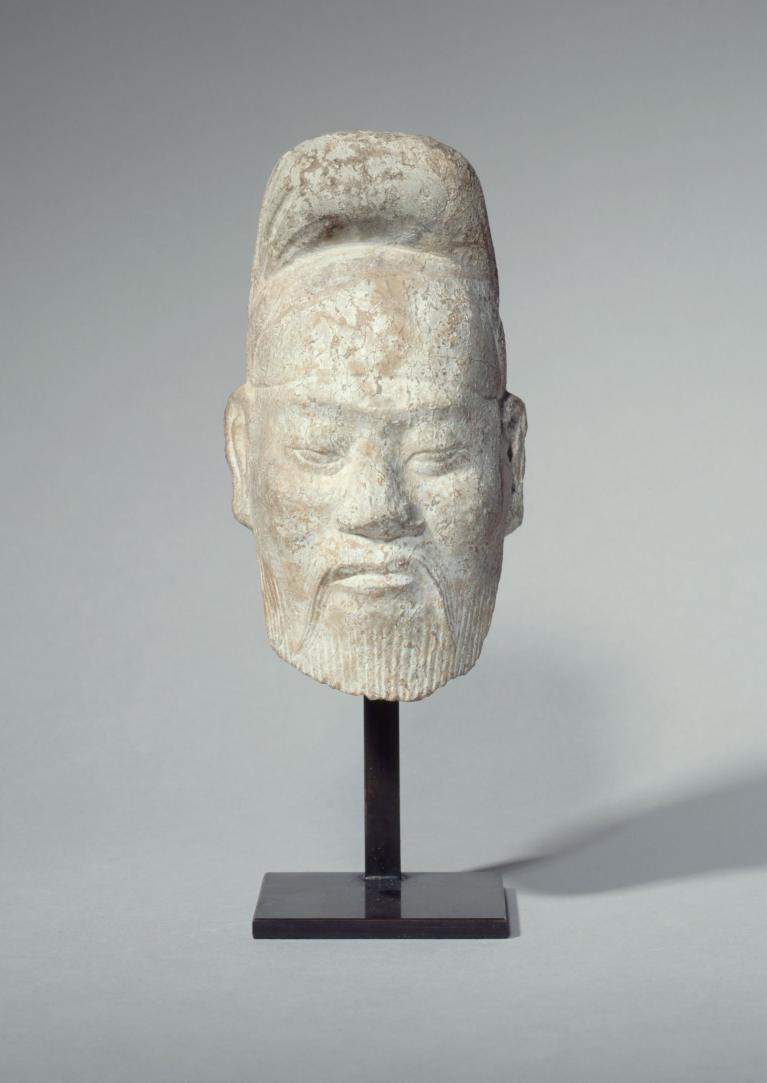

Despite the brevity of the Sui dynasty, it played a major role in artistic development, paving the way for stylistic renewal in the following era. To strengthen the legitimacy of the imperial power, the first Sui emperors built luxurious palaces in their capital. The first emperor Wendi (581-604), an ardent defender of Buddhism, commissioned the building of monasteries in every province and sculptures in gilt bronze, sandalwood or stone. Buddhist sculpture perpetuated certain styles of the Northern dynasties, but a new orientation towards a more pronounced realism is visible in the small gilt bronze statues. Where tomb statuary was concerned, the mingqi from the early part of this period are similar in certain respects to those of the previous Northern Qi dynasty, but in the late Sui period, dress style evolved, and potters began to use transparent straw-coloured glazing instead of the former painted polychrome.

Tang dynasty

The Tang period (618-907) is often called a golden age of Chinese civilisation. The stability brought about by the Sui enabled the new rulers to extend the country’s borders, particularly towards central Asia, and to improve security along the Silk Roads that linked China to the Middle East. The capital, Chang’an, became the largest city in the world at the time, drawing travellers, artists, tradesmen and monks from all over Asia. It was a crossroads for Persians, Arabs, Indians, Turks and Uighurs, who introduced new thinking, religions (Nestorianism, Mazdaism, Manichaeism, Islam), dress and exotic decorative motifs that the Chinese aristocracy lost no time in adopting. These influences spread to Korea and Japan. Pilgrim monks, including the famous Xuanzang (602-664), brought back Buddhist texts from India and contributed to the multiplication of religious currents, including Tantrism and Chan (Zen in Japanese). The reign of Gaozong (649-683) and that of Empress Wu Zetian (Wuhou) (r. 690-704), his wife, probably constitute the height of the Tang era. However, the victory of the Muslims on the banks of the Talas River in central Asia (751) and the rebellion of General An Lushan (755-763) severely impacted the empire, eventually ruined by numerous peasant revolts resulting from extreme poverty and recurrent famines. The great persecution of Buddhism (842-845) put an end to the various forms of artistic expression that it had spawned. Monasteries, statues and religious objects that were part of the proselytising were all destroyed and monks and celebrants returned to civil life.

Although only two temples survived this persecution (Nanchansi and Foguangsi, Shanxi), fortunately many sculptures did. They testify to the Indian influences of the Gupta period: the divinities became more sensual in appearance, with gentle, serene round faces and “wet” drapery following their bodily contours. Their flowing movements reflected a greater concern for realism, visible in the muscular forms of the temple guardians.

The tombs were exceptionally rich. Numerous recent excavations have revealed wall paintings depicting life at court, and terracotta mingqi with lead glazes coloured with metallic oxides, representing aristocratic activities and evoking journeys along the Silk Road.